Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

The first time we see Simon, he's fainting, and things go downhill from there. From passing out to throwing up to hallucinating to getting bloody noses, Simon is a walking mess. But he's anything but weak.

Power in All the Wrong Places

Simon may be a little timid, but he's a compassionate guy. A "skinny, vivid boy" (1.267), Simon's innate goodness comes out in his actions. He recovers Piggy's glasses when they fly off his face (post-Jack's punch), he gives Piggy his own share of meat, and he helps the littluns pick fruit: "found for them the fruit they could not reach, pulled off the choicest from up in the foliage, passed them back down to the endless, outstretched hands (3.138). And, of course, he doesn't turn into a primitive savage and go around killing things.

He's also wise, mature, and insightful to the point of being prophetic. He's the only one (except Piggy) who understands the beast:

Simon, walking in front of Ralph, felt a flicker of incredulity—a beast with claws that scratched, that sat on a mountain-top, that left no tracks and yet was not fast enough to catch Samneric. However Simon thought of the beast, there rose before his inward sight the picture of a human, at once heroic and sick. (6.140)

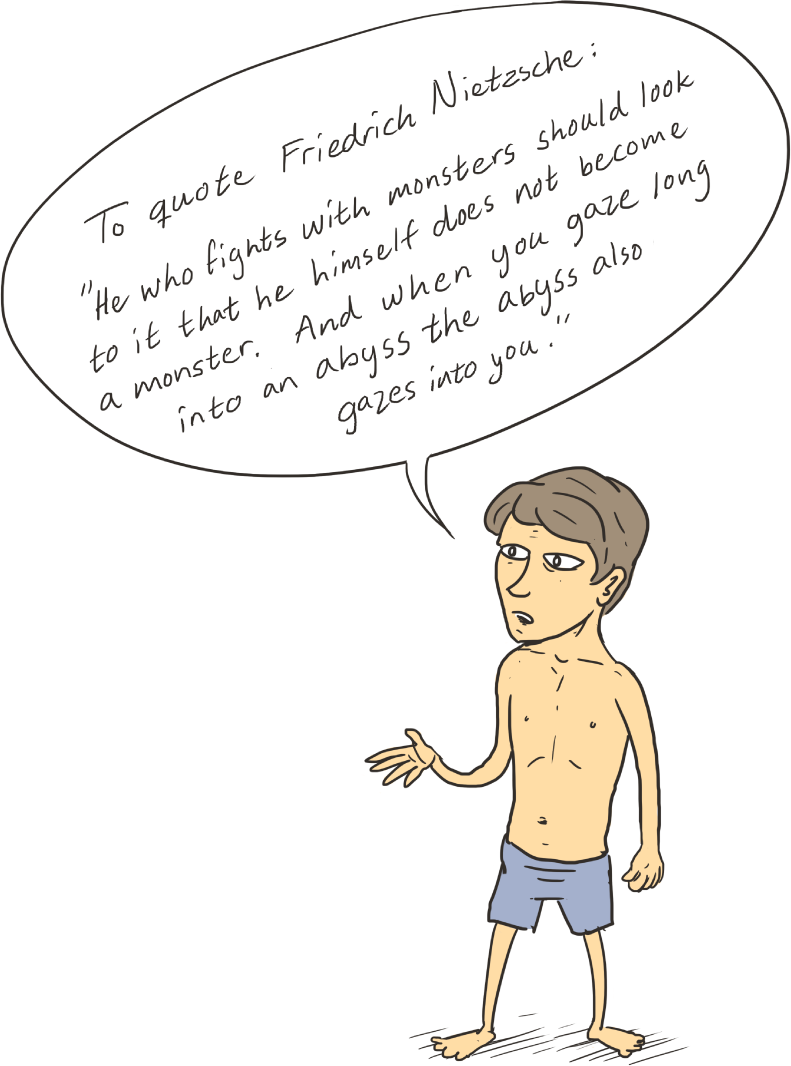

Simon, from his little leafy meditation cave, gets it: the island is changing them. Being afraid of the beast turns them into beasts. If you're having trouble understanding this, let's literalize it for you: he's basically saying that being afraid of an enemy makes you do such horrific things that you turn into the enemy yourself. And by "you," we mean "nations" and "governments." Sound familiar? It should. It's the same kind of argument that some people make today about the War on Terror.

Pig on a Stick

But Simon's freaky wisdom doesn't mean he's immune to the island's effects. Hallucinating and probably dehydrated (that "swollen tongue" is a good giveaway [8.327]), he imagines—we think—the severed pig's head talking to him. And that means Simon is even wiser than we thought, because all of the head's lines are actually his own, like this:

"Fancy thinking the beast was something you could hunt or kill! … You knew, didn't you? I'm part of you? Close, close, close. I'm the reason why it's no go? Why things are what they are?" (8.337)

Simon is the only boy to truly grasp that "the beast" is just all the negative, horrible aspects of mankind. And his "I'm the reason why it's no go" is a direct answer to the question Piggy posed several pages earlier: "What makes things break up the way they do?" (8.265). Simon does have all the answers—but no one's listening.

Of course, there's also the remote possibility that the talking pig's head isn't a mere hallucination—it's the actual Lord of the Flies, Beelzebub the Devil, evil incarnate, talking to Simon via a severed noggin. If this is true, Simon loses points for not coming up with the intelligent insights on his own. On the other hand, he gains quite a few points back for being like Jesus.

Christ Figure

Yep, we've got a Christ-figure on our hands. To start with, his name is Simon, which happens to be the name of one of the twelve apostles. Simon started out as Simon until Jesus decided really his name should be "Peter" instead, because "peter" means rock—and Simon was the "rock" on which Jesus would build his church. If you glance at our "Nutshell," you'll notice that Lord of the Flies is a response to an earlier and much more cheerful boys-on-a-desert-island book, The Coral Island. Golding even borrowed the names Ralph, Jack, and Peterkin. Except "Peterkin" ended up as "Simon."

And then there's Simon's affinity for meditation, his kindred spirit-ness with animals, his "suffer the little children unto me" attitude (think about the fruit-picking), and his ability to prophesize, like when he tells Ralph that Ralph will get home, and sort of suggests that he himself won't.

Having established that, we can go back to our pig's-head-on-a stick scene and compare it to Jesus's visit to the Garden of Gethsemene the night before he was crucified. And when we say "visit," what we really mean is long and solitary mental suffering, much like Simon undergoes the night before he meets his own untimely death. Simon, like Jesus, is "thirsty," and later "very thirsty," and although the text doesn't say it, we can only assume that at one point later he is very, very thirsty. He's also sweating, having a seizure, and bleeding profusely from his nose.

So, if Simon's "night before" matches up with Jesus's "night before," then does Simon die for the sins of the boys? Are they somehow saved by his death? It's hard to say. But it does seem meaningful that he alone had the knowledge of the beast's true nature, he alone had the potential to save the boys from themselves and their fear, and they basically kill him for trying to spread the good news.

The tragic part (well, the especially tragic part) is that Simon says the beast is "only us" and then gets pegged as the beast himself—even though he's the least beast-like of any of the boys. The question is whether, like Jesus, being non-beasty makes him more or less human.

Simon Timeline